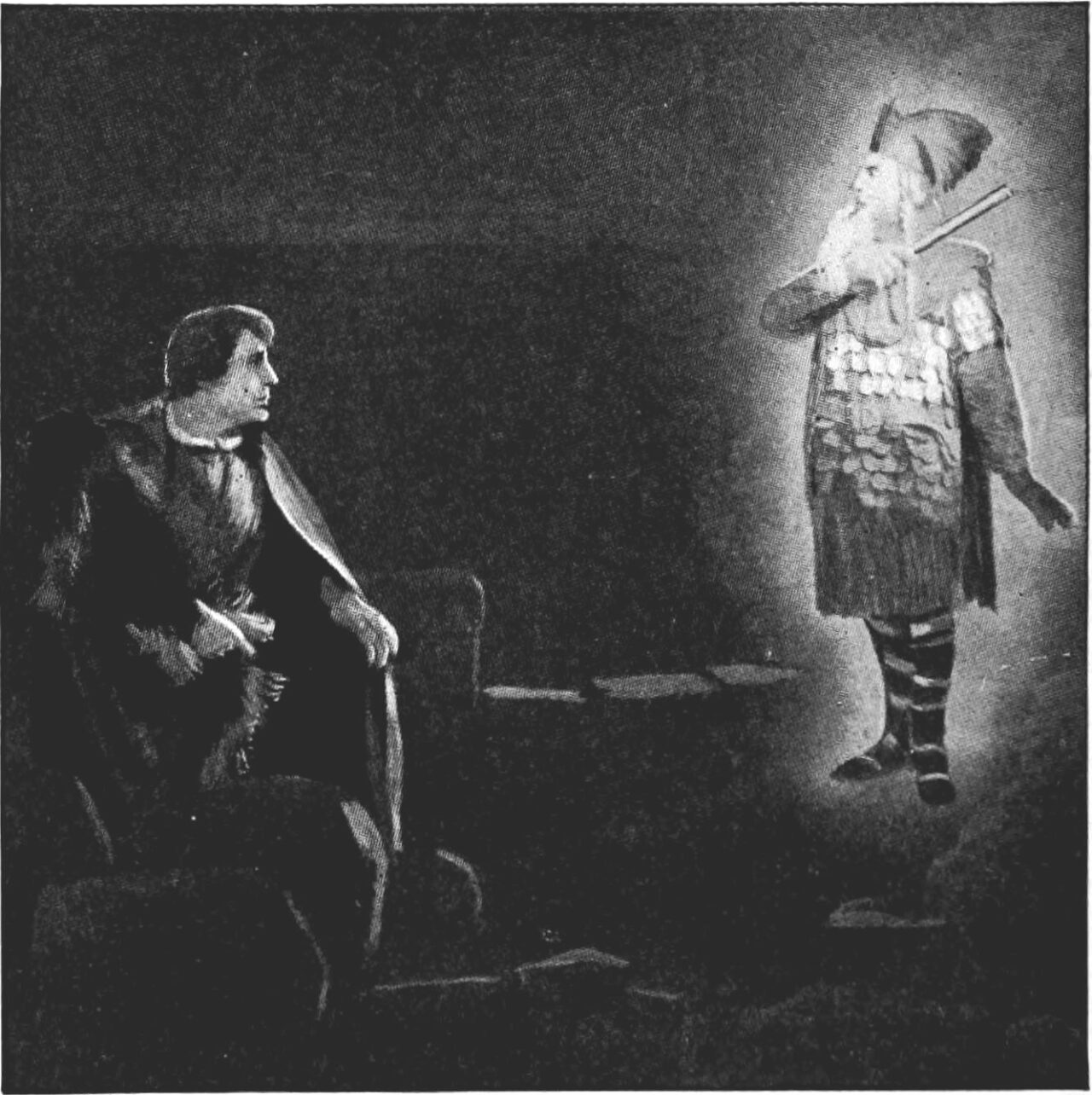

In his play Hamlet, William Shakespeare deliberately presents the ghost of King Hamlet as mostly a just apparition; however, there do exist some potentially ambiguous or otherwise “evil” characteristics of the ghost that tinge its apparent purity.

The prevalence of evidence, as described by Lewes Lavater in his essay “Of Ghosts and Spirits Walking by Night,” proves the king’s ghost overall as good. For example, by the time Hamlet encounters the ghost in Act 1 Scene 4, the ghost has made three appearances, to which Lavater would reply: “we should not give credit as soon as we hear but one sign, but await to hear the same thrice repeated” to prevent the Devil from casting delusions. The three visits of the ghost, witnessed by multiple people, confirm not only the validity of the ghost, but also its intent to bring a message and a warning, not to terrorize or deceive. Furthermore, Lavater mentions that a good ghost can take the form of a deceased person and offer advice or revelations, which King Hamlet does with Hamlet: he informs Hamlet of his poisoning at Claudius’s hands and the necessity for Hamlet to avenge his “murder most foul” (1.iv.33). As Lavater predicts, a good spirit “will at the beginning somewhat terrify men:” Horatio remarks that “It harrows me with fear and wonder” when the ghost appears, startling, but not harming, the watchmen (1.i.51). Building upon Lavater’s comments, Horatio gives key descriptions of the ghost: with his beaver up, Horatio can see the ghost’s “countenance more in sorrow than in anger”—hardly Lavater’s “evil angels…hurtful and enemies to men” (1.ii.247). Horatio, the honest confidant, clearly identifies that the ghost’s appearance does not threaten; rather, it appears to need to share something sorrowful. Thus, the ghost seems more pure and virtuous.

Notwithstanding his laudable traits, the ghost’s speech and actions paint a hazy picture of his true intentions. The ghost appears to Horatio, Marcellus, and Barnardo in Act 1 Scene 1 at the very end of the night, just before dawn’s warm fingers creep over the eastward hill. According to Lavater, good ghosts appear in the brightness of the sun, and so by appearing right at the threshold of the day, the ghost does not fall into the “purely evil” or “purely good” category. As the ghost leaves, Marcellus comments that the ghost “startled like a guilty thing,” again reinforcing the air of ambiguity around the ghost’s purpose (1.i.163). In King Hamlet’s speech, the ghost tells Hamlet of his “prison house” with its “sulf’rous and tormenting flames,” referring to his sufferings in purgatory—a place worse than Heaven, but better than Hell (1.v.6,19). He instructs Hamlet to murder his uncle Claudius, who, like Cain, murdered his brother out of envy in a holy garden. While Claudius’s actions certainly deserve punishment, charging young Hamlet as executioner strays into a moral gray area between killing for justice and killing for revenge—the former pure and the latter sinful. Additionally, the ghost’s command does not meet Lavater’s first test to judge spirits: its presence does not comfort Hamlet, as he laments, “O cursed spite / That I was ever born to set it right!” (1.v.210-211). Failing Lavater’s second criterion, the ghost cries his refrain “Swear” not in a sweet melodious voice, but in a jagged one full of anger. The ghost also never acknowledges any sin beyond “the blossoms of my sin” and lacking his Last Rites, missing the mark on the “humility” test (1.v.83). Thus, the ghost fails to meet most of the specifics of the four criteria Lavater describes to prove his truth, and the characters who interact with the ghost feel an uneasy suspense.

While he appears sincere and nonthreatening, the ghost’s enigmatic nature suggests a corruption of even the purest of kings and prevents the audience from completely trusting the ghost.

This essay was my response to Mrs. Selfridge’s assignment for AP Literature, which was to argue the nature of the presentation of King Hamlet’s ghost to the original Elizabethan audience based on the text of Hamlet and Lewes Lavater’s essay “On Ghosts and Spirits Walking by Night,” with only an hour of time to write and a strict one page limit.